Bobby Petrino has a knack for making his exits noteworthy. He signed a 10-year contract with Louisville and left for the Atlanta Falcons five months later. After a terrible start to his time with the Falcons, he decided he'd had enough, posted laminated farewells to all the players in the locker room, and left for Arkansas. He had a good tenure with the Razorbacks but lied to his bosses about an affair with a staffer, which only came out because he crashed his motorcycle. The lasting image of not just the scandal, but Petrino's Arkansas tenure, is the neck brace he wore to a press conference after the crash.

Petrino's lone year at Western Kentucky was far more mundane, unfortunately. He got in, he won eight games to show he still had it, and he got out. And for a while, it seemed like his second crack at the Louisville job was going to be just fine: He won 34 games in four years. As part of an exceptional 2016 season for the Cardinals, Lamar Jackson won the Heisman. It was all going smoothly.

And then Petrino just gave up. In 2018, Louisville lost eight games by 21 points or more, finishing winless against ACC opponents. Petrino didn't see the end of the season, as the school decided after allowing 77 points to Clemson that it was worth paying Petrino's ludicrous $14 million buyout. The news broke of his firing while his pre-taped weekly television show was on.

The scroll of Bobby Petrino being fired came across during the airing of his Coaches’ show pic.twitter.com/lAWShlWwSV

— Matt Jones (@KySportsRadio) November 11, 2018

Missouri State is Petrino's current home. Unfortunately, since it's an FCS program that was so willing to the Bobby Petrino experience that they hired him, I don't expect we'll see another high-profile, extravagant flameout.

But I want to focus on that last season with Louisville. It's hard to find a more immediate or steep collapse in the last decade than Petrino's 2018. Unsurprisingly, the school took a major step back in recruiting. After averaging roughly the 34th-best class in the country over the previous four years, Louisville fell to 70th in the 2019 recruiting rankings.

In the first part of this study, we finished by establishing a positive relationship between a team's single-season winning percentage and how good their recruiting class is both that year and the following year. It wasn't very strong, but it appeared to be there.

What I want to do this time is look specifically at the extreme ends of the spectra of winning and recruiting, though — still excluding Group of Five and Blue Chip Ratio schools, and still sticking to the Playoff era, but trying to find the seasons and classes that really stick out within our population.

We'll start with the latter aim: What are the best and worst classes these schools have had, and what caused them?

To do that, we first have to determine what the best and worst classes in our sample were. We're going to start with wRoAA, the stat introduced last time to measure the average rating of the players in a recruiting class, compared to our population's average rating. The "w" means the stat has been weighted to account for yearly fluctuations across the whole sample.

What we're going to do next is compare each class' wRoAA to the average wRoAA posted by that school between the 2014 and 2022 recruiting cycles. Nothing too complicated here; just simple subtraction:

wRoAA over Team-Specific Average = single-season team-specific wRoAA - team-specific wRoAA across whole sample

The reason we're doing this is to account further for the fact that for some schools in our sample, recruiting significantly better (or worse) than the national average is the norm. Tennessee recruits better than any other team in our study; since 2014, their weighted ratings have been .029 better than the rest of the field. That's about twice as good as Nebraska (.014 wRoAA), a school that has a massive national fan base and still often signs 4-star recruits.

If we set a new baseline specific to every team, we'll be able to see who has outperformed their standard, rather than just who has a high standard. Instead of .029, or .014, or -.004, the baseline for every team will be 0.

The last thing we're doing to the data is finding the z-score of team-specific wRoAAs. A z-score is the number of standard deviations away from the mean that a number is.

Let's talk through that. Oregon State's yearly wRoAA marks are in the top row of the following chart. The far right cell of this row contains the average of those nine figures.

| Click to enlarge. |

The bottom row contains the Beavers' wRoAA relative to the average you see in the top right cell. It's simple: subtract the average from 2014, from 2015, and so on. As established, doing this for every team will always give us an average wRoAA over team-specific average of 0 in the bottom right cell. The reason is that the numbers in the bottom row will always add up to 0, and 0 divided by anything will always be 0.

The standard deviation of the numbers in the bottom row is a measurement of how spread out these numbers are from 0. Their z-scores represent how many standard deviations they are away from 0. In Oregon State's case, the standard deviation rounds to .006. The Beavers' 2018 class, as an example, is roughly two standard deviations below their overall average, so that class' z-score is about 2.

If that's still a bit too complicated, the short of it is this: A z-score between -1 and 1 is not very notable. Anything above 2 or below -2 is rare. Something beyond 3 or -3 is exceptionally rare. (See this handy chart showing a normal distribution. The percentages represent the proportion of a population we should expect to see within a given range of standard deviations.)

To find the best and worst classes in our population of 414 total classes, we need to set a line that will give us a sample that is both small enough to be exclusive and large enough to be informative.

This part is inexact. If we only use classes with z-scores of 2 or more, or -2 or less, that gives us just 13 classes. While that makes up the most extreme 3 percent of our population, that's too small a sample from which to take lessons. So we'll bump the threshold down a bit to 1.5 standard deviations from 0, which is equal to about 12 percent of the population — or 51 classes. That should be a big enough sample.

Below is some key information about this sample, broken down by what side of 0 a single class' z-score is: how many classes there are; their average z-score; their winning percentage from the previous season (Y-1), the current season (Y), and the two following seasons (Y+1 and Y+2); as well as information about the tenures of the head coaches.

I've collected the coaching data because a coaching change typically has a negative immediate impact on recruiting. Not only were you likely bad enough for your coach to be fired; you are probably bound to lose some of the prospects who committed to the outgoing coach, and the incoming staff has to scramble a bit to assemble a full class.

We can see already there is a link. Teams with especially bad recruiting classes by their standards average roughly 4.6 wins per season the year of that class, which is significantly worse than the other three years we're examining. Among coaches in the sample who no longer have these jobs, the average remaining tenure is shorter after an especially bad recruiting class than it is after an especially good one.

We can break down that last point further. Coaches often last only five or six years at a job. If there's plenty of time until a given coach's tenure falls apart, the classes they sign don't show up in this sample as negatives — unless they exit unexpectedly. In this sample, we have eight classes with negative z-scores and coaches in their last or second-to-last year. We have five classes with positive z-scores and coaches with the same amount of time left. Those five are:

- 2019 Arkansas (+2.13) — Chad Morris left SMU before the world could see if he was really building something there. But his years as a Texas high school coach gave Arkansas a short-term boost in recruiting, even after going 2-10 in his first season. The wheels fell off entirely the next season, though, and Morris was fired before he could win a conference game.

- 2016 BYU (+1.60) — Bronco Mendenhall leaving BYU for Virginia was a surprise. However, there weren't yet two signing days, so announcing his resignation on December 5 meant that his successor, BYU alumnus Kalani Sitake, had enough time to keep the class together. It likely helped how consistent the Cougars had been: Mendenhall won eight or more games nine times. Sitake didn't have to sell recruits on sticking with him for a rebuild. Additionally, the pool of players considering BYU may be small enough that an unexpected end-of-season coaching change doesn't impact recruiting as much as it might at other schools.

- 2014 Kansas (+1.92) — This class' rating is skewed by he commitment of 4-star running back Traevohn Wrench, who signed a letter of intent to play at Kansas but instead spent the 2013 season at a junior college. When Charlie Weis was fired followed the following fall, the Jayhawks' recruiting cratered: The 2015 class had a z-score of -1.85.

- 2018 Louisville (+1.52 z-score) — Hey there, Bobby! As covered, the Cardinals went 8-5 in the 2017 season that preceded this signing class, then followed that up with an abominable 2-10 record. Their 2019 class is one of our extreme negative z-score examples (-1.77).

- 2016 Mississippi (+1.96) — Hugh Freeze should not be mocked or disparaged for the fact Mississippi paid recruits to get a top-five class. He should be mocked and disparaged for his brazen wannabe-televangelist posturing, for messaging people on Twitter if they criticize him or his boss, and for being stupid enough to call an escort service from his university-issued phone. That last bit is what got him fired just two years after going 10-3 and signing that top-five class.

These were all unusual cases. In general, you can see that the most definite way the time a coach has left in his tenure affects recruiting is if he is on his way out.

|

| Restating an important caveat: The above chart is based just on data from our sample of 51 classes with extreme z-scores. |

The correlations demonstrate that there is a significant relationship between posting an exceptionally good or bad recruiting class and how much a team won that season or the season before. R-squared suggests winning percentage explains as much as 10 percent of a team's z-score. At the same time, there is no relationship between this recruiting metric and winning percentage in following seasons.

Those two trends line up with a similar chart I included at the end of this study's first part. It makes sense on the surface: A lot of teams in the Power Five's middle class, the population we're examining, have a big year due to one or two good classes peaking as upperclassmen, and then they return to their mean or even have to reset once those experienced players are gone. The shine stays on for a year, but unless the team keeps winning, that recruiting bump fades. That more or less lines up with the original hypothesis.

But the work so far in this post is backwards-engineering recruiting successes and failures. The last thing we're going to do is look at on-the-field successes and failures, the best and worst seasons in our population, and see how their recruiting fared.

Once again, we have to set some benchmarks for what qualifies as our "best" and "worst" seasons. We'll be using the winning percentages of every team in our population. From there, we will find each team's average single-season winning percentage over the eight seasons we're studying, which will inform a new set of z-scores.

Ideally, we would keep the standard we used for identifying especially good or bad recruiting classes for identifying good and bad seasons: 1.5 standard deviations in either direction from the average. However, that would only give us 31 seasons with which to work, which is less than a tenth of the population. I'd feel more comfortable with a larger sample, so the threshold will instead be 1.25 standard deviations.

Based on cursory examination of the sample, though, I saw some seasons that probably deserved to be considered on the extreme end but weren't included. One reason is that certain programs consistently win so much that, by winning percentage, an unequivocally great season doesn't stand out that much from the pack. This included 2016 Wisconsin, a team that won the Cotton Bowl but wouldn't make our sample because a .786 winning percentage isn't that far from their .733 average.

In other cases, a program's fortunes have fluctuated so wildly that one standard deviation for them is considerably higher than those of most teams. Across our 368 seasons, the average standard deviation in winning percentage is .159. The highest, Baylor's, is .294, which can be easily understood by looking at a graph of their performance since 2014:

After firing Art Briles, the Bears needed a total rebuild. Matt Rhule achieved that and then some. When Rhule left for the NFL, Dave Aranda had to dig the Bears out of a new hole. He won a Big 12 title in his second season. It's been decidedly up-and-down.

We can't go strictly by z-scores, then, which means being a little less scientific and adding more criteria. To hit our z-score threshold, Baylor would need to go undefeated for one of their peaks to be included in our sample. So we're going to add another provision: Teams that win 11 games will also count in our sample.

There are another few things to cover, but we'll do that after establishing the final criteria for what we'll call a "boom" season or a "bust" season:

- Boom season — z-score of winning percentage is greater than or equal to 1.25, AND the team's raw winning percentage is greater than or equal to .615 (minimum eight games played); OR the team won 11 or more games

- Bust season — z-score of winning percentage is less than or equal to -1.25, AND the team's raw winning percentage is less than .500 (minimum eight games played); OR the team won two or fewer games (minimum eight games played); OR the team won zero games

- Kansas exception: A Kansas team can only count as a bust if they won zero games

The winning percentage provisions were to take care of teams who didn't have a truly great or awful season but would have shown up otherwise, such as 2015 and 2021 Texas Tech (a 7-6 record in each case, with a z-score of 1.36). A .615 winning percentage is equivalent to an 8-5 record, which for a program like Kansas or Vanderbilt would count as a major achievement (if they got there). On the other end, we couldn't really count 2014 Iowa's 7-6 season (-1.53 z-score) as a disaster, could we?

The minimum games threshold was to eliminate a few teams, mainly in the Pac-12 who posted extreme winning percentages without playing many games during the pandemic-affected 2020 season. I didn't want to throw 1-3 California in the bust pile or consider 4-2 Colorado as a boom. But 0-5 Arizona, who crashed and burned as hard as any team possibly can? If Kevin Sumlin's Wildcats don't belong here, I don't know who does.

Similarly, winning two games or fewer seems like a fair line to designate as a busted season. A 2-10 season would be worse than the average winning percentage of every team in our sample except Kansas (who have averaged 1.75 wins per year since 2014). Going 2-8 in 2020 was enough for South Carolina to pay a nearly $13 million buyout (during a pandemic!) to fire Will Muschamp.

We will make one more exception for Kansas, though: Since a 2-10 season would actually improve their winning percentage in the Playoff era, the only way the Jayhawks can make it on our list of busts is if they did not win a game in a given season. When their average is a disaster for most programs, it's the only step we can take.

After setting our rules, we have a sample of 46 boom seasons and 48 bust seasons. That's basically a quarter of our total population. Some notable seasons will have missed the cut, but we've tried to account for where our programs' averages lie. If those averages took a dip before a program slid into its nadir — hello, Scott Frost's Nebraska and Geoff Collins' Georgia Tech — then we have to accept that. Our sample is large enough and doesn't need to be expanded any more to cover every good or bad year.

Here is a summary of that sample:

And here is each type of season's average z-score of wRoAA over team-specific average, repackaged in a bar graph. One standard deviation is represented by bars in either direction along the y-axis.

As you can see, on average, a team in a boom season sees recruiting improve both during and especially after that year. But the range of outcomes is much wider in Y+1 than it is during Y.

We can certainly find more cases of a team's recruiting getting a bump after a big year. TCU had an underwhelming 11-14 start to life in the Big 12 but in 2014 broke out. An insane and controversial game at Baylor was the Horned Frogs' only loss, and they won the Peach Bowl. There was an immediate payoff, as their 2016 signing class set a program record by finishing 21st in the nation.

After Christian McCaffrey torched Iowa to close a 12-2 season for Stanford, the Cardinal posted the highest recruiting z-score in our sample (+2.4) the next year. A 10-win season for Kentucky in 2018 turned into seven 4-star signings the next December. The 2019 Minnesota and 2020 Indiana teams discussed in Part I of this study, and a few others that won't be highlighted here, are additional examples. All the teams I've mentioned so far also saw drop-offs in Y+2, which lines up with the idea that the breakout bump is temporary.

But the effect is not universal, which is why we see that large standard deviation. The most common reason is that teams that break out tend to regress in subsequent years. There's no guarantee that you can hold on to prospects when you're missing a bowl. Paul Johnson followed an Orange Bowl title with a 3-9 season at Georgia Tech. The season after a Playoff appearance, Michigan State also went 3-9. A 2016 Pac-12 South title for Colorado was followed by a much more Colorado-like 5-7. Syracuse upset Clemson and won 10 games in 2018, earning Dino Babers a contract extension, but Babers hasn't had a winning season since. All of these teams saw their recruiting return to earth, if not descend deeper.

Nearly every team saw their winning percentage go down the year after a boom. (This excludes 2021 seasons, obviously.) Only about half of the whole group, however, saw their recruiting z-scores go down as well.

We can make an argument, though, that there should be a stronger relationship than is apparent on our scatterplot, that how much you regress on the field affects how much you get hurt while recruiting.

Three of our eight biggest losers in winning percentage had their boom seasons during 2019. Those three — Baylor, Cal, and Minnesota — all saw sizable recruiting bumps, though, which was not true for most other schools that took similar steps backward between Y and Y+1. Their Y+1 years, of course, were the 2020 season, when teams played abbreviated schedules and had to sit players due to COVID cases. Under these circumstances, recruits might have been willing to give teams some benefit of the doubt.

We don't even have to throw out the 2019 teams to see a trend, though. Nineteen of the 36 boom seasons in question were followed by seasons of .500 or better. On average, these teams' recruiting z-score changed by +.7. Eleven of them gained at least one-tenth of a standard deviation on their usual output.

Contrastingly, the other 17 teams — those with Y+1 record under .500 — saw their recruiting z-scores decrease by an average of .4 standard deviations. Just six gained at least one-tenth of one, and the three biggest gainers were the aforementioned 2019 teams.

It makes for a handy cutoff, the kind with which we can make an easy rule of thumb: If you have a big season as a non-Blue Chip Ratio Power Five school, you can see an improvement in your recruiting the next year if you're still good enough to make a bowl. While that's not a guarantee, it's a reasonably safe bet that fielding an average or better team will soften the blow on your signing class of inevitable regression to the mean.

How much is that bump worth, anyway? Well, once again, the answer varies. Teams in our boom season group that saw their recruiting rankings outperform their team-specific averages gained around seven spots.

For example, West Virginia's recruiting ranking in the Playoff era averages just better than 41st place. After a big 2016, though, followed by a bowl appearance the next year, the Mountaineers' 2018 recruiting class ranked 35th.

If a team underperformed their team-specific average even after a big year, and the majority of such cases were after a sub-.500 follow-up, then they lost roughly eight spots on average.

Returning to ratings as our measurement, meanwhile: Let's say that a team successfully executes a boom-plus-halfway-decent-sequel combo. And, generously, we'll call the average gain in wRoAA over a team's average in such cases about one standard deviation's worth. The average wRoAA in our population is .009. According to our dataset, the value of a boom season could mean the difference between netting a standard class for Minnesota (-.004 wRoAA, 28th in our population) and a standard class for Maryland (.005 wRoAA, 15th).

To re-establish, though, this is based on the average rating of a commit in a class. While these are significant jumps to make for a team in the middle class, they seem marginal when you look at how the biggest powers recruit. You have to have consistent enough success to raise your profile, or the benefits of large fan and donor bases and history, to break into the top rung of the sport.

Of course, it's much easier to fall apart.

As covered earlier, and illustrated in the above bar chart, for a team that busts, the worst class in our four-year range of observation tends to be the year that collapse occurs. In fact, 30 of our 48 bust seasons are accompanied by negative same-year recruiting z-scores.

Many of the 18 positive z-scores involve coaches early in their tenure: Kliff Kingsbury in his second season at Texas Tech, Dave Clawson's first couple years at Wake Forest, Chad Morris' first full class at Arkansas, and so on. While a coach might not ever turn a program around (we've covered Morris already), he's usually given some patience early in his tenure, with onlookers accepting that sometimes things get worse before they get better.

With that in mind, it's easier to understand only a dozen of our bust seasons ended in the head coach's departure. Of the other 36 seasons, the head coach was in his first three years at the school.

That leaves 10 seasons where the coach both wasn't too early in his tenure to be fired and stayed for at least one more year. Those can be categorized thusly:

- We probably made a mistake with the contract we gave you — 2014 Iowa State (Paul Rhoads), 2016 Arizona State (Todd Graham), 2020 Syracuse (Dino Babers)

- We trust you enough to believe this is a fluke — 2019 NC State (Dave Doeren), 2021 Indiana (Tom Allen, who might turn out to actually belong in the first category)

- We respect you too much to fire you — 2016 Michigan State (Mark Dantonio), 2019 Northwestern (Pat Fitzgerald), 2020 Duke (David Cutcliffe), 2021 Northwestern (Fitzgerald again), 2021 Stanford (David Shaw)

Patience is often fair in these situations. The year after the teams in our sample went bust, their winning percentage improved in all but two cases (2014-15 Wake Forest, 2018-19 Arkansas). Regression from the mean comes for us all, and it isn't always a bad thing.

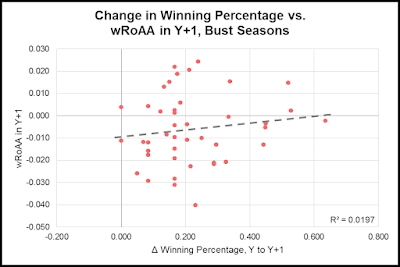

Whether it is as good as we want may once again depend on how successful the follow-up season is. There is a stronger relationship between post-bust winning percentage and Y+1 wRoAA (r = .26) than there is between the margin by which winning percentage improved and Y+1 wRoAA (r = .14). But there is still significant variability.

We can explain a bit of that variability by again asking where the coaching staff was in its life cycle. Our 12 teams who fired coaches mostly saw their recruiting destroyed the same year they busted, but many of them stabilized or got better in Y+1, outperforming their respective average recruiting ranks by roughly five spots. Those that didn't fire their coach saw little appreciable difference between how they recruited either season compared to their typical level.

That doesn't mean that the key to kick-starting your recruiting is firing your coach — at least not in every instance. If he deserves to be fired, then he deserves to be fired. The 12 schools whose coach departed averaged a winning percentage of .160, which is almost a win worse than the .228 mark the schools who kept their coach posted.

Notably, those 10 teams we talked about earlier who kept their coach after a bust season generally took losses in recruiting as well. The same wasn't true for those who had coaches in their first three seasons in charge. Tenured coaches saw their recruiting rankings drop 2.4 spots from their program's average the same year their record plummeted, and non-tenured coaches saw their rankings gain a tenth of a spot. If you've been around for a few years, a bad season can hurt in recruiting more than if you haven't. A known quantity gets less benefit of the doubt.

To bring this all the way back around to our original questions: Will a good season help you in recruiting in the short-term? It can, but you have to show that it's not a blip in order to reap the whole reward. (Either that, or have your breakout or regression year line up with a pandemic.) And that reward won't be turning into a recruiting superpower, but just punching above your weight.

Will a bad season hurt you in recruiting in the short-term? If you're new to the job, it probably won't hurt unless you can't show some proof of concept the next season. If you aren't new, you'll either be fired and ruin your team's recruiting, or you'll keep your job, and once again have to prove yourself.

In either case, "short-term" means short. By two years after your boom or bust season, what you did then doesn't mean as much as what you did recently. That's college football recruiting, though: Always chasing the most current form of your perception, and trying to improve or maintain it as best you can.

All raw recruiting data via 247 Sports.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.